While I was in Kazakhstan in 2004 adopting my youngest

daughter, we stayed in an apartment in Almaty. We were waiting for the bureaucratic wheels to finish

turning for her adoption to be final, which left a lot of time for leisure

activities like reading and napping. Our apartment had been used by many other adoptive families

passing through, and a stash of reading material had accumulated in the living

room. Outdated magazines, chick

lit, etc. But one book caught my

eye: The Malaria Capers by Robert

Desowitz.

I have to insert a disclaimer here: I am a rabid fan of non-fiction. Biography, memoirs, history, you name it. I want to read about real people. I want to see pictures of them, look

into their eyes. I want to learn

about events that really happened.

I don’t know why; who’s to say why we like the things we like. Are our “third culture kid” interests

shaped by the serpentine paths of our lives? Does having seen real history up close and personal make me

more likely to pick up a non-fiction book rather than Danielle Steel’s latest schlock? Probably the subject of another blog entry.

Okay, disclaimer over.

The Malaria Chronicles read like a good spy novel. In our part of the world we know so

little about the devastation wrought by a single little mosquito. We can’t relate to a poor Indian family

who has to walk for a day to get basic medical care. We have to symbolically turn away at the thought of a child

dying an agonizing death from a mosquito

bite. The book talks about the

futile efforts of finding a vaccine against malaria, and the not-so-good hopes for the

future. It doesn’t sound too

good. Politics intervenes, as does

poverty and distance and fear.

When a person has to choose between food and medicine, which do you

think they will pick? Especially

when the medicine will cost a month’s wages? When a stranger comes to their village and tells them

they’re going to stick a needle in their arm and that will possibly prevent

them from getting sick, what do you suppose the reaction will be?

The other day I came across another book called “Pox: An American History” by Michael

Willrich. Another story of how

politics and racism sometimes get in the way of public health. There were compulsory vaccinations of

hordes of people, bickering between the federal and local government over who

was supposed to pay for it all, and a sorely misguided belief that only blacks

and poor whites were susceptible to the disease. It’s a miracle that this disease has been eradicated …

gone.

I’m one of probably millions of kids who carry the telltale

little scar on their arms. I

remember getting the vaccination right before we left for Japan in the

mid-1960’s. My shot “took” meaning

that I developed a huge festering “pock” on my arm. I was not to get it wet. Of course we were going to stop in Hawaii for a few days

before going on to Tokyo, so guess who had to sit by the pool watching everyone

else have a good time?

We went to the most interesting places to get our shots all

over the world. There was a place

near the Belgian Royal Palace where we went in Brussels. The American Embassy in Manila. A clinic in downtown Tokyo. All this to protect us against scourges

like yellow fever, typhoid and the dreaded cholera. The cholera shots were especially egregious as we had to get

one, and another a week later, then every six months thenceforth. My arm hurt like a bear for days, and

someone at school would inevitably smack me right there. Of course I hated the shots, but mom

would regale us with lively stories about constant diarrhea and vomiting that

dehydrated you so that you died a long agonizing death. She embellished (more likely it wasn't embellished) the misery, I suppose, so that we wouldn’t

complain too loudly about being poked yet again.

When the brother of a friend came down with hepatitis right

after I had slept over, mom escorted me to a clinic in Brussels for the dreaded

gamma globulin shot. They keep

that stuff in the refrigerator until it’s the consistency of jello. Then they put it in the biggest

hypodermic needle they have and inject it into your buttock. Slowly and agonizingly. I still remember the pain of that one. Of course, it was nothing compared to

the pain I would have endured had I developed hepatitis. Is it sad that I know that if your urine is the color of coca-cola, you most likely have hepatitis?

Before going to Kazakhstan the first time, my husband and I

went to Passport Health to update all of our shots. I sat on the table and had six (count them, SIX) shots,

three in each arm. It was

explained to me that most people in the western world may get all the necessary

childhood immunizations, but rarely do they get boosters as adults. (Unless one steps on a rusty nail and

is encouraged to get a tetanus shot).

I felt pretty good knowing that I had all the hepatitis, polio, DPT and

MMR shots updated.

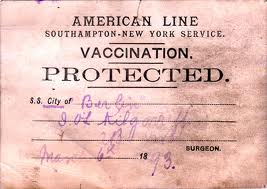

|

| Remember these? |

We in the west take our health for granted. We don’t give it a second thought when

we are bitten by a mosquito.

However, too many dread diseases still exist in the world. It’s easy to turn off the TV when

there’s a story about an epidemic in a Third World country. We TCKs have endured the slings and

arrows of a multitude of shots against diseases most have never even heard

of. We’ve had classmates who suffered

from polio as children and who walked with crutches through the halls of our

school. We’ve seen children with

rickets and adult survivors of smallpox begging at the side of the road. These diseases are too real to

us. It makes me sad when I hear of

people in the developed world who refuse to vaccinate their children for

whatever misguided reason. It only

takes one case to start an epidemic.

Do we really want to see diptheria make its way back into our

society? Whooping cough? I remember the story of a newly adopted child from China coming down with measles on the flight home. How many people on that packed airplane

were exposed, who may not have had a booster shot as an adult?

We might need to think twice.

No comments:

Post a Comment